For over a century, a bizarre prediction of Einstein’s special relativity – the Terrell-Penrose effect – has remained purely theoretical. This effect suggests that objects approaching the speed of light wouldn’t appear compressed (as per Lorentz contraction), but rotated. Now, researchers have demonstrated this phenomenon in a laboratory setting for the first time, confirming a long-standing quirk of relativistic physics.

From Science Fiction to Scientific Reality

The experiment originated from a thought sparked by H.G. Wells’s 1901 story, “The New Accelerator,” which imagined a drug slowing down time. Researchers wondered if such a slowdown could reveal relativistic effects, specifically the Terrell-Penrose effect, which had only existed in simulations. The breakthrough came through collaboration with the SEEC project, focused on visualizing light’s movement, and the use of ultrafast photography to effectively “slow down” light’s apparent speed.

Why the Terrell-Penrose Effect Matters

The confusion arises from two key concepts: Lorentz contraction (objects shrinking at high speeds) and the Terrell-Penrose effect (objects appearing rotated instead). Early theoretical work by physicists like Anton Lampa and Hendrik Lorentz debated whether these effects would even be visible. Later, Roger Penrose and James Terrell independently calculated that the contraction wouldn’t be observed directly; instead, light travel time differences would create the illusion of rotation. This seemingly counterintuitive prediction remained unverified until now.

The Experiment: Mimicking Relativistic Speeds

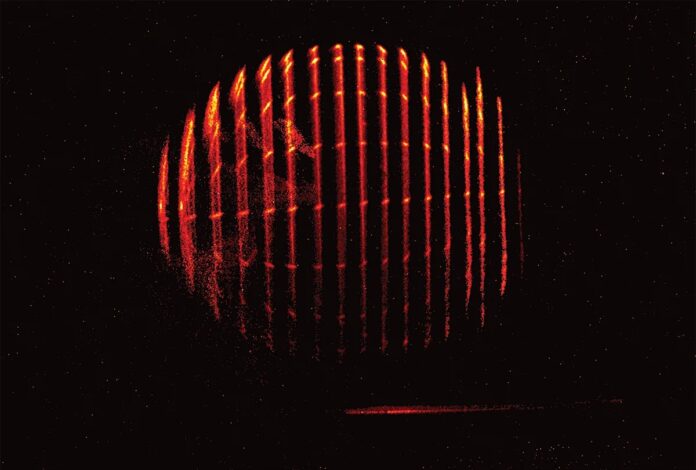

The team used a pulsed laser, emitting light in picosecond bursts, and an ultrafast camera capable of capturing images in just 300 picoseconds. By rapidly taking “slices” of objects – a sphere and a cube – as they moved, they mimicked the distortions expected at near-light speed. The key was the timing: each image captured light from a slightly different moment, creating a time-lapse effect.

To ensure the effect was visible, the researchers intentionally compressed the objects along the direction of motion. Without this step, the elongation would have canceled out the rotation. The sphere was moved at 99.9% the speed of light, while the cube was moved at 80% the speed of light. The resulting images confirmed the Terrell-Penrose effect: both objects appeared rotated, matching theoretical predictions. The cube also exhibited hyperbolic curvature on its edges, a detail predicted in 1970 by Ramesh Bhandari.

Implications and Future Research

This experiment not only validates a century-old prediction but also opens new avenues for studying relativity. Researchers suggest similar techniques could test time dilation, stellar aberration, and even Einstein’s thought experiments on simultaneity. By artificially reducing the speed of light through rapid imaging, they have effectively brought relativistic physics into the lab, turning science fiction into observable reality.

The success highlights the power of combining advanced technology with theoretical curiosity. This experiment proves that relativity continues to offer surprises, even after more than a century of study.